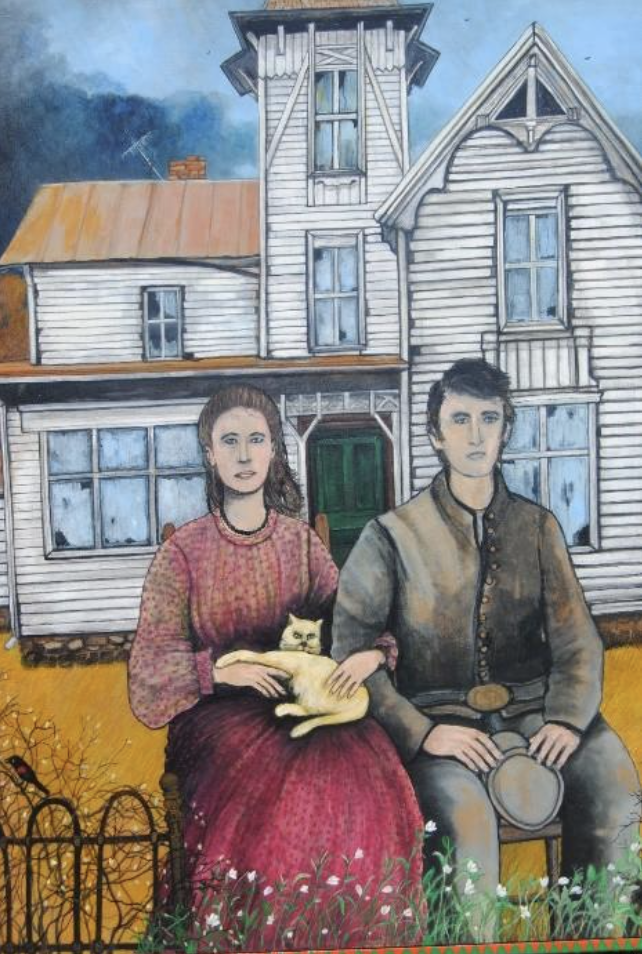

Justin Renteria, American

Untitled, 2018

While this piece is not a direct photograph of mountaintop removal mining in Appalachia, it certainly resembles one. Images of the impact of mountaintop removal share striking similarities to this artistic interpretation of a mining area, devoid of color, splattered with thick oil, seemingly encroaching on the lush surrounding forests. The impact of coal mining in Appalachia is not dissimilar to this physical landscape. As increased environmental degradation has occurred, these energy industries not only strip natural environments of their resources, they strip the land of its color, both figuratively and literally. Not only are mountain tops and forests turned into dreary wastelands, the surrounding communities are stripped of their cultural connections to the lands that they have inhabited for generations, and non-human animal habitats and ecosystems are decimated. The beauty of the nature of the landscapes and the beauty of the human and non-human animals that reside within them are quickly being destroyed by the expansion of these industries. The priority of the industry is exclusively economic growth and development. All other considerations are rendered irrelevant to the progress of the American economy, regardless of the amount of “color” that is stripped from these regions in the process. Label by Gwyneth McCrae