Gallery Overview

What can be wrong with beauty? Beauty is something that attracts our eyes, brings us pleasure, and oftentimes compels us to contemplate. Some environmental artists, however, are often criticized that the aesthetical value of their images obfuscates the environmental injustice in the sites they photograph. This gallery attempts to offer a critical view of the role of aesthetics in promoting environmental justice, and locate the intersection of aesthetics and politics in works of two photographers.

Debate about Aesthetics in Photography

Environmental justice is a human rights issue. It concerns with communities disproportionately affected by environmental hazards which are usually directly or indirectly caused by polluting industries and government policies and practices.[1]

Edward Burtynsky, BP GULF SPILL © Edward Burtynsky

TJ Demos believes that an aerial view photograph turns the image of the place into a painterly surface of aesthetic pleasure, and thus diverts the attention away from the disproportionately affected communities.[2] In analyzing Adward Burtynsky’s photographs, TJ Demos points out two problems. First, by presenting an aerial view of the site, the photograph makes a universalizing discourse which disavow differentiated responsibilities for the geological changes. It emphasizes the dramatic visuality of the catastrophic oil economy’s infrastructure founded on capitalist growth, which “we as a species,” as Burtynsky says, have created.[3] Therefore, the image universalizes responsibility for climate disruption. Second, such photograph aesthetizes modern industrial pollution, and displaces the scene from the misery of those living in this industrial apocalypse. The aerial shot isolates the poisonous industrial exploitation from its larger socioeconomic and politico-cultural environment, thereby transforming it into an innocuous painterly abstraction. The aesthetical visual pleasure conceals the catastrophic impact of the event on local community and ecology, as well as the social and political forces behind it.

However, aesthetics plays significant role in helping photographers articulate discourses of environmental justice and raise public aware. Instead of presenting an “innocent beauty” as TJ Demos states, photographers’ strategic use of the formal elements on the pictorial surface brings the viewers’ attention to environmental injustice. While the beauty of the photograph entices the viewer, the beauty is held in tension with the power and potential for devastation. As Burtynsky says, [4]

I want to create that tension, have them attracted yet repulsed, to show them the dilemma we’re in

Photographers also deploy aesthetics to address slow violence. The photographers’ task of producing a visual awareness of environmental justice is complicated by the fact that most environmental justice issues are largely invisible. The effect of environmental injustice on its victims is a kind of slow violence, which occurs gradually and out of sight, has delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, and typically not viewed as violence at all.[5] Aesthetics, however, assists to make the narratives dramatic enough to rouse public sentiment.

In the following galleries, two artists deploy aesthetics in raising awareness of environmental injustice. In Salon 1, Subhankar Banerjee uses color and composition to create a visual tension that brings the viewers’ attention to the environmental injustice in the indigenous groups of the Arctic. In Salon 2, Patrick Nagatani combines elements in Japanese woodblock prints with scenes of New Mexico, making use of the aesthetics of estrangement to address environmental injustice in the local communities.

Salon 1 - Subhankar Banerjee

The Beauty of Life and Violence – a New Perception of the Arctic

In this Salon is Subhankar Banerjee’s Arctic series. Banerjee started the series in 2000 with a desire to see areas only accessible with the hired assistance of Native-American guide, longing for the “pristine wilderness” or “last American frontier”.[6] Over the years his romanticized ideas of the Arctic were shattered, and his vision has evolved into a visual exploration of the Arctic’s connection to larger global issues such as resource wars, climate change, toxic migration, and human rights struggles of the northern indigenous communities.

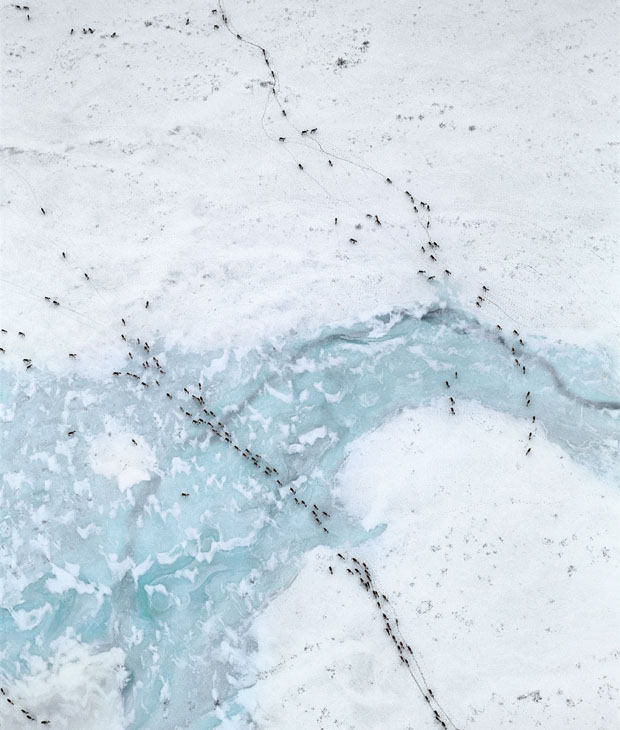

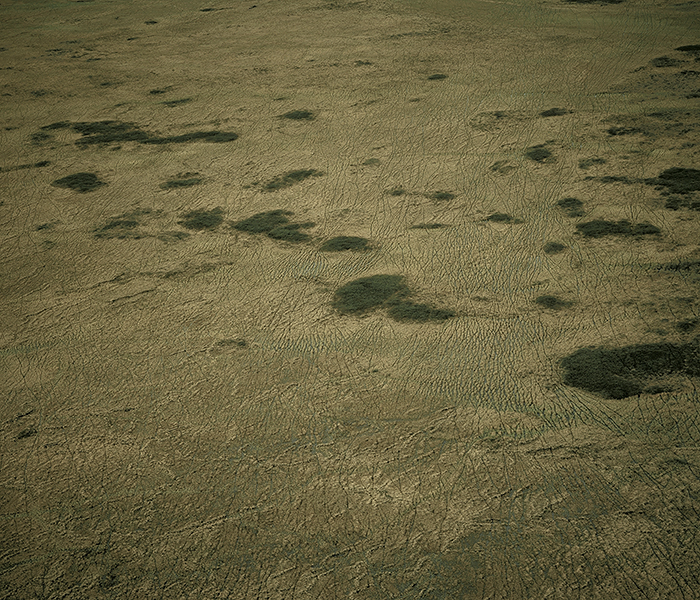

In the series, Banerjee presents the photographs in three sets, based not on geography but on color: white, green/grey, and brown. Banerjee’s use of color counters the notion of the Artic as a vast white nothingness and asks the viewer to reconsider the impact of oil development in the area. The pro-oil-development USA politicians describe the Arctic as ‘flat white nothingness’, ‘frozen wasteland of snow and ice’ and ‘barren wasteland’.[7] These descriptions indicate that the Arctic is a place of ecological fecundity and awaiting capitalist investment to bring forth its full productive potential. In Banerjee’s photographs, however, the Arctic appears as a vibrant environment marked by subtle gradation of color and tone and a variety of shades and hues. In his famous photograph Caribou Migration I, for example, the light blue of the Coleen River and the dark dots of female caribous interrupt the vast whiteness of the land, and compel the viewer to pay attention to the animals belong to the area. The viewer would realize that the land photographed a land with lives, and that to open up this land to oil drilling would greatly impact local ecological system.

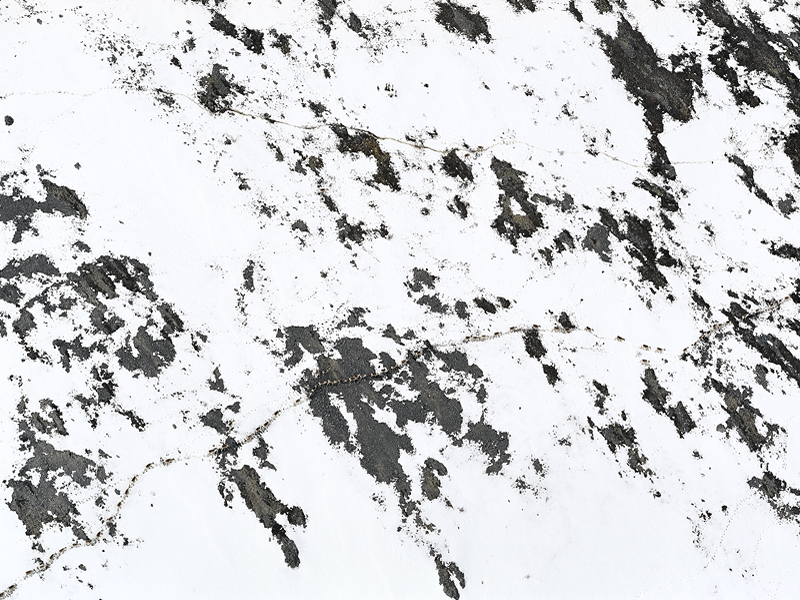

The color and composition of the images of human hunting also bring attention to how human actions constitute vital components of the ecological system. In the Gwich’in and the Caribou, for instance, the intensity of Cariblou blood against the snow-covered arctic landscape in the foreground emphasizes the sacrificial violence of indigenous people’s hunting practices. The scenes of hunting, the stark confrontation of death and violence show that the indigenous groups are not passive beings capable only of genuflecting before nature, but groups that form bonds of exchange and interdependence with the nonhuman world. In this way, Banerjee portrays the Arctic not as an untouched wilderness but as a space where humans have developed complex relationships with their environment.

The beauty of life in the aerial photographs and that of violence in human hunting scene creates a visual tension which compels the viewer to contemplate on the environmental injustice confronted by the indigenous groups. The photo series attracts and repels the viewer at the same time. As Banerjee himself describes: [8]

Three tensions are present:

scale – we stand back to see a large photo, whereas we get close to see a small one

emotion – for most people, seeing migrating caribou over a frozen river and high mountains is attractive, while seeing blood of butchered caribou is repulsive

history – American conservation is rooted in the idea of preserving pristine wilderness untouched by humans, but humans hunt in the wilderness for food.

The aesthetics of the natural land of the Arctic bring the viewers’ attention to the area, and raises their curiosity about the local lives there. The close-up view of the hunting practice of indigenous communities trigger emotional response, and challenge the preconception of the Arctic as a lifeless land. As a result, the visual tension created by the juxtaposition demands the viewer to ponder on the impact of oil development on local communities.

Also, the naming of the photographs reveals the conflictions between oil drilling and the local animals which are closely tight with the daily life of local communities. The titles of photographs juxtapose industrial development and local animals: oil in caribou calving ground (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge – Oil and the Caribou); oil in bird nesting ground (Teshekpuk Lake wetland – Oil and the Geese); coal in caribou calving ground (Utukok River upland – Coal and the Caribou); and oil in whale migration path (Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea – Oil and the Whales). All of these animals are an integrated part of the lives of indigenous communities, as food resources and religious symbols. The impact on the local animals disturbs the balanced relationship between indigenous communities and non-human world.

Salon 2 - Patrick Nagatani

The Beauty of the Uncanny and Displacement in Place

In this salon are selected works from Patrick Nagatani’s Nuclear Enchantment series. Nagatani published the series about the continuing effects of nuclear weapons development in the American Southwest in 1991, at the edge of the Cold War. Nagatani was born in Chicago in 1945, 13 days after the United States attacked Hiroshima, to Japanese-American parents interned in camps during World War II. Nagatani belonged to the Atomic Photographers Guild, a MacArthur-funded documentarian organization dedicated to recording the nuclear age.[9] With the hyper-saturated colors and combination of elements from Japanese woodblock prints with scenes in New Mexica, photographs in this salon capture the uncanny aesthetics in New Mexico under the looming threat of nuclear power, and address the issue of displacement of the local communities.

The sense of uncanniness is related to displacement. In 1919, when Freud originally coined the term “uncanny,” unheimlich in German, he contrasted it with the word heimlich, meaning “homely,” in the sense of the safe or familiar.[1] The uncanny is a sense of unhomely, unfamiliar, and estranged.According to Jean-Luc Nancy, when one is taken out of one’s country, one feels uncanny: one no longer recognize familiar landmarks and customs, and no longer knows one’s way around.[10]

Rob Nixon regards the displacement of communities dwelling at a place as a form of slow violence. As exterior industrial forces alter the environment of a place, the local communities are under the threat of displacement from their living knowledge as the place losses its life-sustaining features. The communities are not physically forced to move out of the place; instead, they are stranded in a place “stripped of the characteristics that made it inhabitable”.[11] Compared with physical displacement, this is more invisible, but this could cause more profound impact on the history and culture of the community, as well as their capacity to self-sustain.

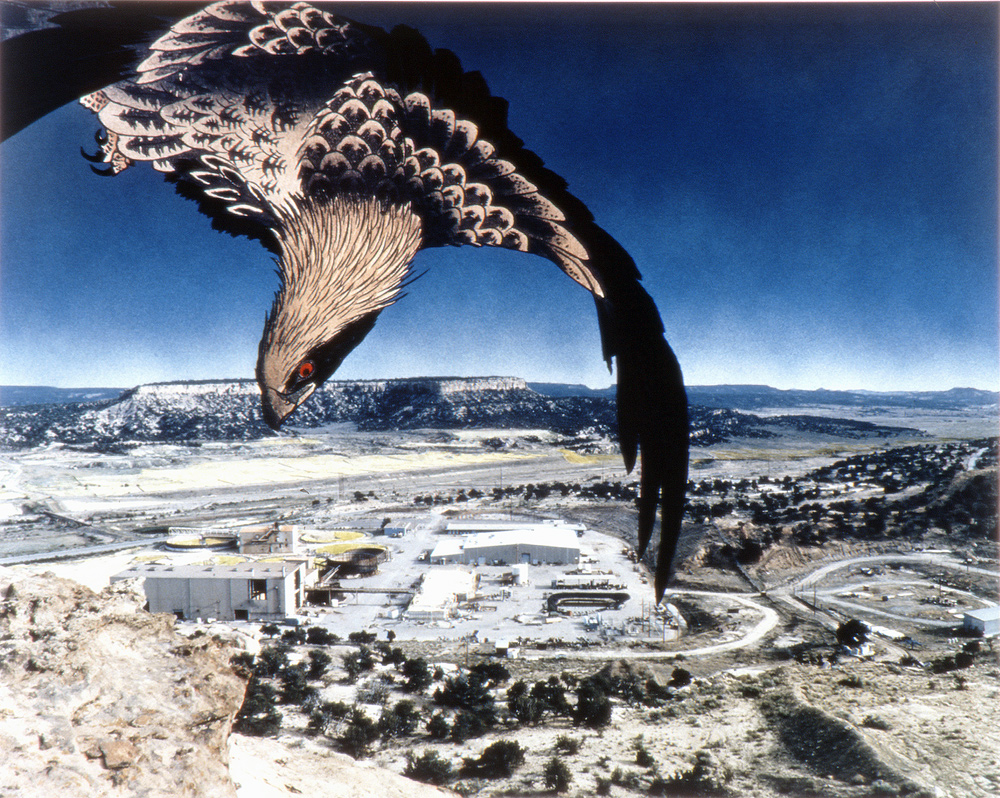

The photographs in this salon investigate the invisible displacement of the people of this state caused by historical and contemporary development of nuclear industry. Nagatani depicts the ways that nuclear weapons make the home of New Mexico uncanny, unhomely, hostile, and strange to its people. The place looks the same, but there’s something rotted out at the core. In the image, a sense of estrangement is achieved through the layering of local scenes with images from the great nineteenth-century Japanese woodblock artist Hiroshige: the color gradation, the composition with little or no middle-ground and the flattened surface are reminiscent of the Japanese aesthetics. Therefore, the viewing experience is an encountering of estrangement: one may find the landscape of New Mexico familiar, and yet the place has been transformed into something strange by the elements from Japanese prints. Here, instead of offering visual pleasure, the use of aesthetics disturbs the viewers’ mind, and challenges them to look into what is under surface of the seemingly peaceful land of New Mexico.

(Image of Hiroshige’s print is from Brooklyn Museum’s online collection.)

In Golden Eagle, Nagatani layers the golden eagle from Hiroshige’s prints on top of an aerial view of the United Nuclear Corporation’s uranium mill in Church Rock, New Mexico. The mill utilized an acid leach process to extract uranium, producing wet radioactive waste. The site is only a mile from the Navajo Reservation which is mainly populated by impoverished Native Aemricans. On July 16, 1979, a dam at the mill broke, releasing 90 million gallons of radioactive material into the Rio Puerco, the main water source for 350 Navajo families.In 1990 when Nagatani produced the work, area residents were still dealing with the impacts of the disaster. [12]

The detailed depiction of the feather on the golden eagle and the composition which emphasizes the foreground are all typical of Japanese prints. Also, the subtle gradations of blue in the sky reminds the viewer of the multi-color woodblock prints technique frequently used in ukiyo-e prints (“painting of the floating world”). Under the sky, however, is the suffered land of Church Rock, instead of the peaceful snowy land of Edo in Hiroshige’s original work. The aesthetical value of Japanese prints, therefore, is in sheer contrast with the struggles of the Navajo community. Just as the golden eagle is displaced from its original setting, the Navajo families have been deprived of their original connection with local water resources.

(Image of Hiroshige is from Brooklyn Museum’s online collection.)

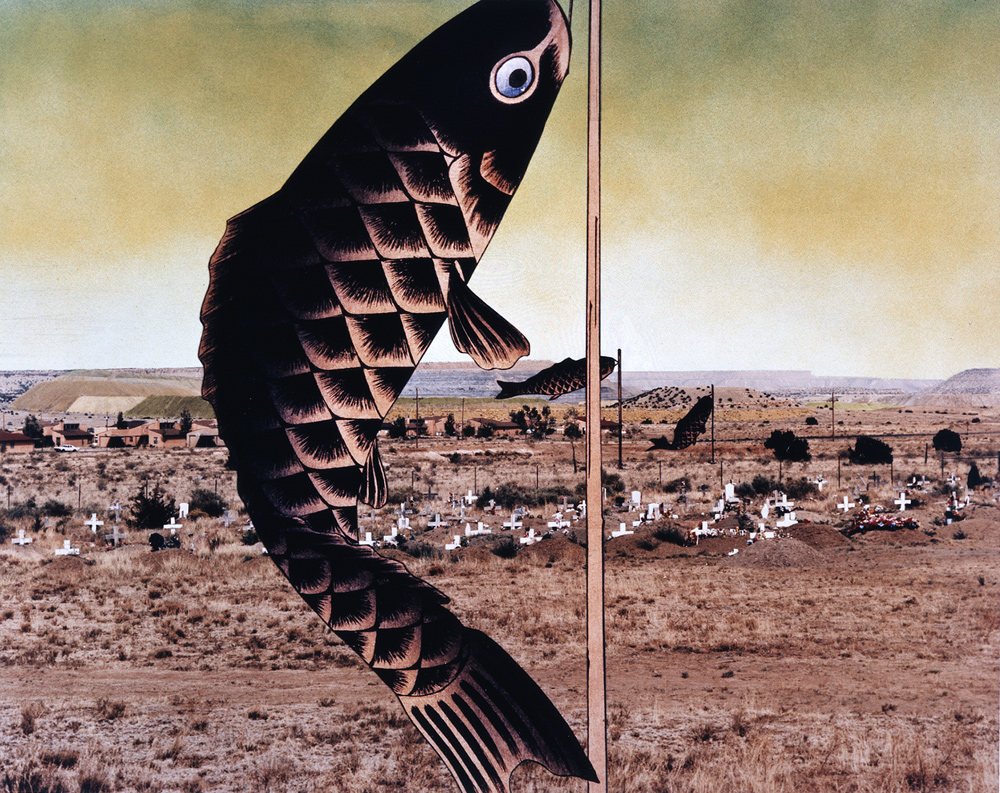

In the Japanese Children's Day Carp Banners, Nagatani layers the golden eagle from Hiroshige’s prints on top of an aerial view of the United Nuclear Corporation’s uranium mill in Church Rock, New Mexico. The mill utilized an acid leach process to extract uranium, producing wet radioactive waste. The site is only a mile from the Navajo Reservation which is mainly populated by impoverished Native Aemricans. On July 16, 1979, a dam at the mill broke, releasing 90 million gallons of radioactive material into the Rio Puerco, the main water source for 350 Navajo families.In 1990 when Nagatani produced the work, area residents were still dealing with the impacts of the disaster. [13]

The detailed depiction of the feather on the golden eagle and the composition which emphasizes the foreground are all typical of Japanese prints. Also, the subtle gradations of blue in the sky reminds the viewer of the multi-color woodblock prints technique frequently used in ukiyo-e prints (“painting of the floating world”). Under the sky, however, is the suffered land of Church Rock, instead of the peaceful snowy land of Edo in Hiroshige’s original work. The aesthetical value of Japanese prints, therefore, is in sheer contrast with the struggles of the Navajo community. Just as the golden eagle is displaced from its original setting, the Navajo families have been deprived of their original connection with local water resources.

Notes:

[1] Robert D. Bullard, “Introduction” and “Environmental Justice in the Twenty First Century,” in The Quest for Environmental Justice, ed. Robert D. Bullard (Counterpoint, 2005), 1-42

[2]TJ Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today(Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017), 61-72.

[3]As cited in TJ Demos, 65.

[4]As quoted in Jannifer Peeples, “Toxic Sublime: Imaging Contaminated Landscapes.”Environmental Communication, vol. 5, no. 4 (December 2011): 380.

[5]Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor(Boston: Harvard University Press, 2011), 1-30.

[6]Yates McKee, “Of Survival: Climate Change and Uncanny Landscape in the Photography of Subhankar Banerjee”, in Impasses of the Post-Global: Theory in the Era of Climate Change(Edited by Henry Sussman, Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2012), 85-86.

[7]Subhankar Banerjee, “Photography’s Silence of Non-Human Communities”, 362.

[8]Patrick Nagatani, “Nuclear Enchantment,” Atomic Photographers Guild, https://atomicphotographers.com/photographers/patrick-nagatani/.

[9]As cited in Jeffery Moro, “Weird Ways of Seeing: Patrick Nagatani’s Nuclear Vision”, Los Angeles Review of Books, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/weird-ways-of-seeing-patrick-nagatanis-nuclear-vision/.

[10]Jean-Luc Nancy, “Uncanny Landscape”, in The Ground of the Image(Translated by Jeff Fort. New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 53-54.

[11]Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor(Boston: Harvard University Press, 2011), 1-30.

[12]Alan C. Braddock and Karl Kusserow, “The Big Picture: American Art and Planetary Ecology”, in Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment(Yale University Press, 2018)

[13]Nagatani, Patrick. A Hot Iron Ball He Can neither Swallow nor Spit out: Patricka Nagatani, Nuclear Fear, and the Uses of Enchantment. Edited by Eugenia Parry Janis. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1991. 36-37.

References

Alan C. Braddock and Karl Kusserow, “The Big Picture: American Art and Planetary Ecology”, in Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment. New Haven:Yale University Press, 2018.

Bullard, Robert D. “Introduction” and “Environmental Justice in the Twenty First Century,” in The Quest for Environmental Justice, 1-42. Edited by Robert D. Bullard. Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2005.

Demos, TJ. Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017.

Demos, TJ. “Climates of Displacement: From the Maldives to the Arctic,” in Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology, 63-99. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016.

McKee, Yates. “Of Survival: Climate Change and Uncanny Landscape in the Photography of Subhankar Banerjee”, in Impasses of the Post-Global: Theory in the Era of Climate Change, vol. 2. Edited by Henry Sussman. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, 2012.

Moro, Jeffery. “Weird Ways of Seeing: Patrick Nagatani’s Nuclear Vision”. Los Angeles Review of Books. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/weird-ways-of-seeing-patrick-nagatanis-nuclear-vision/.

Nagatani, Patrick. “Nuclear Enchantment.” Atomic Photographers Guild. https://atomicphotographers.com/photographers/patrick-nagatani/.

Nagatani, Patrick. A Hot Iron Ball He Can neither Swallow nor Spit out: Patricka Nagatani, Nuclear Fear, and the Uses of Enchantment. Edited by Eugenia Parry Janis. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1991. 36-37.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. “Uncanny Landscape”, in The Ground of the Image. Translated by Jeff Fort. New York: Fordham University Press, 2005.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Boston: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Peeples, Jannifer. “Toxic Sublime: Imaging Contaminated Landscapes.” Environmental Communication, vol. 5, no. 4 (December 2011): 373-392.

Subhankar Banerjee. “Photography’s Silence of (Non)Human Communities,” in All Our Relations. Edited by Catherine de Zegher and Gerald McMaster. Sydney: 18th Biennale of Sydney, June 2012.