Overview: Art and Environmental Justice

At its core, environmental justice asserts environmental problems affect us all, but they do not affect us all equally. The marginalized and disadvantaged segments of the global population (i.e. the poor, people of color, women, and children) bear the heaviest costs of environmental problems that privileged elites create. Since poverty, race, and environmental injustice are intricately linked, environmental justice issues are multivalent. The variety and range of environmental threats addressed combined with the diversity of populations and geographic regions at risk means that environmental justice advocates constantly embrace new contextually-specific issues and aspirations and that the justice they seek is multidimensional. In short, the discourse of environmental justice continually transforms and evolves.

One of the challenges of confronting environmental injustice is bringing it to the public’s attention. Rob Nixon explains in Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (2011) that environmental injustices stems are acts of “slow violence” that are overlooked and underreported:

By slow violence I mean violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all. Violence is customarily conceived as an event or action that is immediate in time, explosive and spectacular in space, and as erupting into instant sensational visibility. We need, I believe, to engage a different kind of violence, a violence that is neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive, its calamitous repercussions playing out across a range of temporal scales… Climate change, the thawing cryosphere, toxic drift, biomagnification, deforestation, the radioactive aftermaths of wars, acidifying oceans and a host of other slowly unfolding environmental catastrophes present formidable representational obstacles that can hinder our efforts to mobilize and act decisively. The long dyings¾ the staggered and staggeringly discounted casualties, both human and ecological that result from war’s toxic aftermath or climate change ¾ are underrepresented in strategic planning as well as in human memory. [i]

In short, environmental injustice has a visibility problem. The majority of environmental abuses fail to draw the attention of the public or the media because they occur slowly and without dramatic calamitous events. Fossil fuels threaten human existence every day, but actually showing this environmental assault to people is next to impossible. Even the catastrophic events of environmental violence (e.g. wildfires, nuclear meltdowns, explosions of offshore oil rigs, and spills at chemical plants) that make immediate headlines in mainstream and social media do not have staying power. Footage is shown, death tolls are given, victims and first responders are interviewed, and then once the spectacle of these catastrophes is over, the public (and subsequently the media) quickly loses interest. Coverage of the recovery from an environmental crisis and the slow violence of its after effects gets pushed to the margins.

Visual language is a powerful tool that is currently underused by environmental justice movements. Art can help the public witness the unseen by giving a visual sensory component to the slow violence of environmental injustice and its impacted populations. In Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and the Environment Today (2017), art historian and cultural critic T.J. Demos evaluates different forms of visual culture and their effectiveness in promoting environmental justice. He explains that images taken at a great distance (e.g. satellite images) are neither simple nor direct for the general public. In addition, extreme distance from the subject matter (e.g. the image of planet earth) causes viewers to be detached from the issues at hand rather than personally vested in them. Demos finds images that make environmental injustices into works of visual splendor are also not effective since their abstractions of the subject matter can result in environmental awareness taking a back seat to formal analysis. He asserts the most successful uses of visual culture invite viewer participation. The scale and placement of street art confronts both privileged and disenfranchised populations alike as they move through their daily routines, encouraging (if not demanding) audience involvement by commanding a position in their everyday activities.

Rob Nixon interview with DemocracyNow.org (August 2018): Government Inaction on Climate Change Is “Slow Violence: That Hits World’s Poor the Hardest”

The Power of Street Art

The street has always played a historic role in the promotion and expression of personal, social, and political opinions. It is a meeting point for society as well as a site where new ideas challenge established norms. It is the backbone of every community, where people share both a common address and lived experience. It is also a place where confrontations occur, and scores are settled. Urban art specialist Mary McCarthy explains the impact of street art in “Street Art as a Tool for Social Change,” a 2017 post from her Huffington Post UK blog:

In terms of style, street artists utilise their day to day environment as a canvas like no other movement before. Any surface becomes a canvas. Street artists go beyond the confines of the expected, or art school training, to create works on any background - from walls to railings, from wood to metal, from buildings to vehicles…. Politically, with the street as their medium they can voice their thoughts instantly, changing rhetoric and opinion through their direct communication to the people. Street art work can become influential very quickly - Shepherd Fairey's iconic Hope image was created in one day and very soon after was adopted by pro Obama supporters and reproduced widely. Socially, street artists work is now being used as a proactive tool for change, transforming areas across the globe….

The street as a medium has also ensured that street art has a far-reaching appeal, enabling a generation to appreciate and engage with art who normally wouldn't have been inspired to go to a gallery. The work itself is approachable, appeals to all ages and through the very nature of the content of street art, you don't need a formal art education to understand it. Street artists have ensured that art is accessible to all, whether you choose to engage with it or not. …The evolution of this to a Street Art Movement where so many use their art for good, for political comment, and to envision a better future, beyond the commercial, and even the aesthetic, in my opinion proves that street art has changed generations like no other art movement to date and it is the most multi-faceted and prolific movement in the history of art.[ii]

By existing outside of art institutions (both literally and figuratively), street art enjoys a unique position that allows it to openly challenge normative societal practices and offer hope to marginalized populations, which makes it a perfect tool for addressing environmental injustice. Like environmental justice concerns, street art is also multivalent, offering a multitude of visceral visual reactions to a wide variety of concerns. Since they are outdoors, the street art works are also subject to environmental conditions and the slow violence of ecological change. The genre attempts to subvert institutionalized expectations and reclaim the popular sphere by using a platform that reaches a broader audience than the traditional curated museum setting. By placing powerful images in the quotidian human environment, the audience has unrestricted access to these images, and they cannot avoid the large-scale of their content. Street art is ever-present, addressing contemporary issues in public for long durations since the works exist until they are painted over, demolished, or simply erode away. Murals exist alongside the denizens of neighborhoods and communities as important components of their individual and collective identities. The lasting impacts of these works make them an ideal art form to reveal the long-term effects and slow violence of environmental injustice.

Salon 1: Environmental Justice Warriors

According to a July 2018 report by international NGO Global Witness, “It has never been a deadlier time to defend one’s community, way of life, or environment. Our latest annual data into violence against land and environmental defenders shows a rise in the number of women and men killed last year to 207 - the highest total we have ever recorded. What’s more, our research has highlighted agribusiness including coffee, palm oil, and banana plantations as the industry most associated with these attacks… Countless people around the world are under threat for standing up to the might of large corporations, paramilitary groups, and even their own governments.”[iii] Environmental defenders are on the frontlines of the global movement to fight climate change and protect the planet. The majority are members of indigenous groups who work both voluntarily and professionally to fight environmental injustice. They struggle to preserve fragile ecosystems and safeguard human rights against more powerful institutional and corporate forces who act unethically, irresponsibly, and illegally.[iv]

By standing up for sustainability, biodiversity, and justice, environmental defenders literally put their lives on the line. They become targets for a litany of crimes committed by corrupt governmental and business entities that are leveling forests for monoculture crops and poisoning soil and water with their mining operations. The defenders fight for the environment as well as the health and future of affected communities despite the risk to their own safety. Based on the Global Witness report, approximately 60% of the environmental killings recorded in 2017 occurred in Latin America, making it the world’s most dangerous place to be an environmental defender, with the Philippines and Africa coming in as the second and third, respectively.[v]

Sources:

Why 2017 Was the Deadliest Year for Environmental Activists

Almost Four Environmental Defenders a Week Killed in 2017

Salon Spotlight: Activist Berta Cáceres (1973-2016)

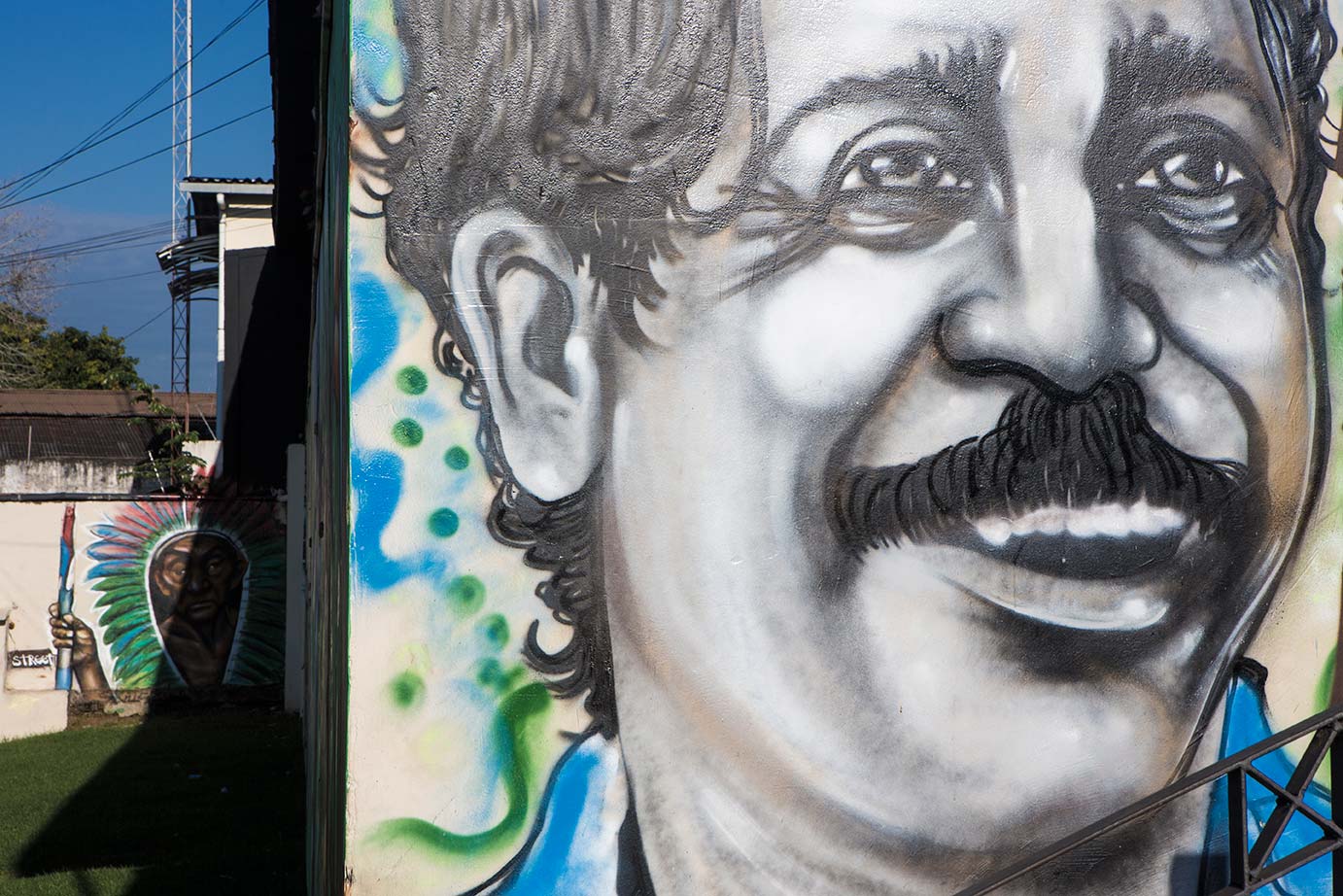

A popular art form such as street art is perfect for celebrating the efforts and sacrifices of these popular environmental heroes. The assassinations of environmental defenders elicit both professional and grassroots street art responses, as seen in the case of Berta Cáceres, a murdered Honduran environmental activist and member of the country’s indigenous Lenca population. Cáceres started a campaign against the Agua Zarca Dam, “a joint project of Honduran company Desarrollos Energéticos SA (DESA) and Chinese state-owned Sinohydro, the world’s largest dam developer. Agua Zarca, slated for construction on the sacred Gualcarque River, was pushed through without consulting the indigenous Lenca people—a violation of international treaties governing indigenous peoples’ rights. The dam would cut off the supply of water, food and medicine for hundreds of Lenca people and violate their right to sustainably manage and live off their land.”[vi] Cáceres rallied the Lenca people to fight the dam, ultimately forcing Sinohydro to pull out of the project and putting her life in danger. She received the Goldman Envrionmental Prize for her efforts in 2015 (see biography video below). After receiving countless death threats as a result of her activist work, gunmen stormed her home on March 3, 2016 and killed her. To date, evidence indicates that her murder was a military operation carried out under orders of the Honduran political and economic elite.

Street art responses to Cáceres’ death occurred around the globe, and they ranged from large-scale murals created by professionally-oriented artistic collectives to smaller popular and self-taught artists’ works. Regardless of their training and skills, these artists use public spaces to commemorate their fallen hero, solidifying her iconic status while channeling their grief and outrage into communal artworks celebrating her life and accomplishments. The images serve to bring attention to Cáceres’ activist work as well as status as an environmental martyr. The majority of the murals include a representation of Cáceres herself, frequently depicted with text that speaks to the legacy of her activism, such as “Berta Vive” (“Berta Lives”) and “Berta Cáceres volverá and será millones” (“Berta Cáceres will return and she will be millions”). Some murals feature indigenous symbolism, such as ears of corn, as well as scenes of the Rio Blanco, the sacred river that Cáceres fought to protect. Included elements of tropical vegetation (e.g. palm fronds, flowers) and butterflies speak to the flora and fauna of her indigenous Lenca region. Through the works of art, Cáceres lives on, remaining part of the daily lives of people around the world who still seek to continue her work as well as justice for her murder (see link below for Berta Vive trailer).

In a country with growing socioeconomic inequality and human rights violations, Berta Cáceres rallied the indigenous Lenca people of Honduras and waged a grassroots campaign that successfully pressured the world's largest dam builder to pull out of the Agua Zarca Dam.

Berta Vive Trailer

Street Art Tributes to Other Environmental Defenders

The notoriety of Berta Cáceres activism and murder has stimulated an outpouring of street art to celebrate her life and accomplishments. Unfortunately, her violent death is not a unique case, as the Global Witness report shows. Other slain environmental justice advocates have also been celebrated by street artists around the world, such as Chico Mendes, Edwin Chota, and Ken Saro-Wiwa. Artist Eduardo Kobra, however, commemorates the work of the living in his tribute to Raoni Metuktire, the chief of the Brazil’s indigenous Kayapo people. Chief Raoni has campaigned for the demarcation of indigenous lands in the Amazon, which are threatened by hydroelectric dams, illegal mining and the expansion of soya plantations.

Kayapó leader Raoni Metuktire talks about threats to uncontacted tribes in Brazil and the impacts of the controversial Belo Monte dam. Find out more.

Chico Mendes was a Brazilian environmentalist and labor leader who fought to protect the Amazon rainforest and the indigenous people who live there.

The United Nations Climate Conference is being held in Peru, which is now the world's fourth most dangerous country for environmental defenders. Four were killed in September alone. In a brutal incident in a remote region of Peru's Amazon rainforest, leading indigenous activist Edwin Chota was ambushed as he traveled to neighboring Brazil for a meeting on how to address the region's illegal logging crisis.

In 2014, Posterboy put up this tribute to murdered activist Edwin Chota in Lima, Peru.

Salon 2: The Capitalocene

Changing the Discourse: Moving from Anthropocene to Capitalocene

In 2000, Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer formulated the concept of the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch defined by human activity as a major force fundamentally transforming the biosphere. The 1700s marked the end of agricultural age and a shift to thermo-industrial human activity. This significant transition in the development of enterprise set mankind on a far different trajectory powered by fossil fuels, innovative thinking, and a new market-based economic order that began to fully flower as Western Civilization entered the Industrial Revolution. The shift from wind and water to fossil fuels caused a dramatic rise in human energy use, with industrial societies using four to five times more energy than their agrarian predecessors.[vii]

Steffen et al. explain the effects of this industrial shift on the environment in “The Anthropocene: Conceptual and Historical Perspectives” (2011):

Exploiting fossil fuels allowed humanity to undertake new activities and vastly expand and accelerate the existing activities. The most important example of the former is the capability to synthesize reactive nitrogen compounds from unreactive nitrogen in the atmosphere, an energy-intensive process. In essence, this fossil fuel-driven industrial process (the Haber–Bosch process) creates fertilizer out of air. An example of the latter is the rapid increase in the conversion of natural ecosystems, primarily forests, into cropland and grazing areas owing to mechanized clearing technologies. Another example is the increase in the diversion of water from rivers through the construction of large dams.

The result of these and other energy-dependent processes and activities was a significant increase in the human enterprise and its imprint on the environment. Between 1800 and 2000, the human population grew from about one billion to six billion, while energy use grew by about 40-fold and economic production by 50-fold. The fraction of the land surface devoted to intensive human activity rose from about 10 to about 25–30% [56]. The imprint on the environment was also evident in the atmosphere, in the rise of the greenhouse gases CO2, CH4 and nitrous oxide (N2O). Carbon dioxide, in particular, is directly linked to the rise of energy use in the industrial era as it is an inevitable outcome of the combustion of fossil fuels.[viii]

The steady increases in population, mechanization and urbanization alongside the emergence of capitalist corporate entities focused on turning larger and larger profits expanded industrial development as well as greenhouse gas emissions throughout the first half of the twentieth century. After World War II, human enterprise accelerated, causing a dramatic increase in the rate at which mankind has impacted the environment known as the Great Acceleration.

The logical extension of the Anthropocene framework is an assertion that mankind as a whole has had a detrimental environmental impact across the globe, but this is hardly accurate. In fact, the Anthropocene is a sweeping generalization that is fraught with inaccuracy and ambiguity. While acknowledging mankind’s share of the blame in ecological degradation is certainly a necessary step in attempting to remedy environmental problems and injustice, all human populations do not have the same impact. As Rob Nixon explains in “The Anthropocene and Environmental Justice” (2017):

Homo sapiens may constitute a singular actor, but it is not a unitary one. Seventy billionaires now call New York City home, the same city where 30 percent of children live in poverty. Oxfam reports that in 2013 the combined wealth of the world's richest eighty-five individuals equaled that of the 3.5 billion people who constitute the poorest half of the planet. And a 2013 study concluded that since 1751— a period that encompasses the entire Anthropocene to date—a mere ninety corporations have been responsible for two thirds of humanity's greenhouse gas emissions. That's an extraordinary concentration of Earth-altering power.[ix]

It is hardly fair to blame all of the world’s population for environmental impacts caused by the neoliberal capitalist policies of the industrialized world. The concept of the Anthropocene, with its contention that mankind as an entity causes ecological damage, asserts an equitable culpability across socioeconomic and cultural boundaries that is simply incorrect. The wealthiest nations produce the most greenhouse gases, but the poorest countries produce substantially less pollution and suffer the most severe impact of climate change. This disproportional impact of consequences caused by ecological degradation is the crux of environmental injustice. The inaccuracy of the term “Anthropocene” calls for a term that more accurately address the cause of negative environmental impacts, especially since the acceleration of the mid-twentieth century. Given the dominant role of corporate capitalism and neoliberal economic development in environmental destruction, a more fitting term for the current geological epoch would seem to be the Capitalocene.

Street Art Responses to the Capitalocene

Large corporations tend to be major players in the mainstream art world, funding museum exhibits and commissioning works of art as an extension of their corporate interests. While business entities certainly sponsor mural projects, not all street artists choose to accept corporate patronage, preferring to stick closer to their roots as independent, free-thinking street taggers who subversively express themselves in the urban environment. As a vernacular art form, street art is a powerful vehicle for commenting on the environmental abuses of Capitalocene since it operates outside of capitalism’s sphere of influence and patronage. Whether attacking specific corporate entities and practices or the capitalist system as a whole, street art brings the slow violence and social inequity of Capitalocene to the attention of the masses.

Salon Spotlight: BLU

Italian street artist BLU’s work began like that of many street artists as illegal activity on the exteriors of abandoned buildings. He chooses to remain anonymous, keeping both his identity and his face hidden. Considered among the ten best contemporary street artists by the British magazine The Observer, he began his career as a politically incorrect artist in the late nineties, creating street art in the outskirts of that Bologna of social centers and disused industrial warehouses. His extremely irreverent images incorporate an extensive use of outline and flat planes of color, reminding viewers of comic book imagery. BLU also does not allow photographs or give interviews. The few glimpses of his personal life and artistic process come from the videos he posts on his website, his blog, and a documentary film MeGuNiCa (2009), which chronicles his 2008 painting exploits in Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. BLU is well-known for his street art around the world, and his work has been appeared in festivals, galleries, museum shows, books, and magazines. A staunch critic of social and environmental injustices, his work makes scathing attacks on global institutions and power structures as well as specific corporate entities. He strives to create murals that are contextually relevant to their sites as well as the plight of the people who live there. [x]

An excerpt from the documentary "Megunica", directed by Lorenzo Fonda. Megunica is a film about a trip taken by a team of filmmakers with artist Blu through Mexico, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Argentina. trt: 80 minutes. Format: MiniDV trailer and more infos at www.megunica.org

Juan "Accidentes" Dominguez is on his biggest case ever. On behalf of twelve Nicaraguan banana workers he is tackling Dole Food in a ground-breaking legal battle for their use of a banned pesticide that was known by the company to cause sterility. Can he beat the giant, or will the corporation get away with it?

A collaboration between Blu and OsGemeos for Crono festival in Lisboa (Portugal) soundtrack by osgemeos, studiocromie, koyo and blu (recorded after dinner) available on the dvd BLU 2010: http://www.artsh.it/shop1/index.php/ see the finished wall here: http://blublu.org/sito/walls/2010/006.html os gemeos blog: http://osgemeos.com.br/ about blu: http://blublu.org

Salon 3: Creative Destruction

Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950) coined the term “creative destruction” to describe the process of industrial change in the name of corporate growth and profits. It is a paradox of progress: the constant churning of the free market causes industries to vanish, the ruination of businesses, and job loss, but it also generates wealth and newer, better products in the societies where it operates. This is not the full picture, however, as the wealth and access to jobs, better products, and higher living standards is limited to the upper echelons of society.[xi]

Herein lies the paradox of progress. A society cannot reap the rewards of creative destruction without accepting that some individuals might be worse off, not just in the short term, but perhaps forever. At the same time, attempts to soften the harsher aspects of creative destruction by trying to preserve jobs or protect industries will lead to stagnation and decline, short-circuiting the march of progress. Schumpeter’s enduring term reminds us that capitalism’s pain and gain are inextricably linked. The process of creating new industries does not go forward without sweeping away the preexisting order.[xii]

But, this is not all that gets swept away. The push to produce new products for consumption, from technology to clothing to entertainment, has direct environmental impacts. Factories, industries, and pollution wreak havoc on the environment as they produce new consumer goods for profit. People buy these goods, whether they need them or not, in order to meet certain societal expectations. In the competition of capitalist society, your possessions define you, so consumers strive to have the newest and the best of everything to construct their identities and assert their social status, whether they need these items or not. As a result, people buy new goods even if there is nothing wrong with their old possessions, generating unnecessary waste which ends up in landfills. Along with corporate and consumer waste, environmental injustice is another by-product of creative destruction. The populations traditionally living alongside these industrial sites, their waste dumps, and public landfills tend to be poor people of color that may depend on these industries for jobs while simultaneously contending with the side effects of capitalist production that threaten their health, their lands, and their ways of existence. In the push to create and consume more, the damage of creative destruction is ultimately focused on people who cannot defend themselves against it.

This salon is a play on Schumpeter’s term “creative destruction.” The artists included here are generating images that speak to the destruction of our planet in uniquely creative ways. From strategic placement in areas affected by global warming’s rising water levels (e.g. BANKSY and Martín Ron) to works foreshadowing the destruction of the earth and its environment (e.g. Louis Masai and PØBEL and Atle Østrem), these artists seek to bring public attention to the effects of waste and excessive consumption on the planet. The salon’s spotlighted artist, BORDALO II, literally creates his art from the destruction caused by capitalist consumption and production by using discarded objects to create his large-scale relief works.

Salon Spotlight: BORDALO II

Portuguese artist Artur Bordalo (Street Name BORDALO II) (b.1987) creates mixed media sculptures of animals out of found materials, including garbage cans, broken appliances, old car parts, old doors, siding, leftover construction materials, and even entire cars. His sculptures, made almost entirely from trash, speaks to consumer society’s wasteful habits as well as the negative impacts of trash on the environment and animal life. [xiii] His subjects are animals of all sizes that are vulnerable to harm at the hands of consumer society, from tiny rodents and foxes to deer and wolves.

I belong to a generation that is extremely consumerist, materialist and greedy. With the production of things at its highest, the production of "waste" and unused objects is also at its highest. "Waste" is quoted because of its abstract definition: "one man's trash is another man's treasure." I create, recreate, assemble and develop ideas with end-of-life material and try to relate it to sustainability, ecological and social awareness.[xiv]

Big Trash Animals is a series of artworks that aims to draw attention to a current problem that is likely to be forgotten, become trivial or a necessary evil. The problem involves waste production, materials that are not reused, pollution, and its effect on the planet. The idea is to depict nature itself, in this case animals, out of materials that are responsible for its destruction. These works are built with end-of-life materials: the majority found in wastelands, abandoned factories or randomly and some are obtained from companies that are going through a recycling process. Damaged bumpers, burnt garbage cans, tires and appliances are just some of the objects that can be identified when you go into detail. They are camouflaging the result of our habits with little ecological and social awareness.[xv]

To create his works, he collages the materials he finds into the shape of an animal, and then he spray paints it to unify the shape and complete the piece. The forms range from assembled relief sculptures against the sides of building and fences to freestanding forms in the round. Using these unique methods to create works that are both surprising and sustainable, BORDALO II provides a new dimension for street art both literally and figuratively. His 2017 series “Attero” (the Latin word for “waste”) features smaller scale trash animal figures on old doors and siding. Many of his works are created in and around Portugal, but he has also created works in other countries.

References

[i] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, (Harvard University Press, 2011), 2-3.

[ii] Mary McCarthy, “Street Art as a Tool for Social Change,” Huffington Post UK, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/mary-mccarthy/street-art-as-a-tool-for-_b_15329722.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer_us=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_cs=LJBE_uF7hrP_kRKhor1ZVA, accessed November 13, 2018.

[iii] “At What Cost? Irresponsible Business and the Murder of Land and Environmental Defenders in 2017,” Global Witness, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/at-what-cost/, accessed November 15, 2018.

[iv] Ibid, accessed November 15, 2018.

[v] Ibid, accessed November 15, 2018.

[vi] “Berta Cáceres,” The Goldman Environmental Prize, https://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/berta-caceres/, accessed November 10, 2018.

[vii] Will Steffen, Jacques Grinevald, Paul Crutzen, and John McNeill, “The Anthropocene: Conceptual and Historical Perspectives,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 369 (2011): 848.

[viii] Ibid, 848.

[ix] Rob Nixon, “The Anthropocene and Environmental Justice,” in Curating the Future: Museums, Communities and Climate Change (Routledge, 2017), 29.

[x] “BLU to Niscemi Supports NO MUOS” (translated from Italian to English using Google Translate), Erdoto108, http://www.erodoto108.com/blu-a-niscemi-supporta-i-no-muos/, accessed November 19, 2018.

[xi] Richard Alm and W. Michael Cox, “Creative Destruction,” The Library of Economics and Liberty, https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/CreativeDestruction.html, accessed December 1, 2018.

[xii] Ibid, accessed December 1, 2018.

[xiii] Lucy Wang, “Artist Turns Urban Trash into Amazing Animal Murals,” Inhabitat, https://inhabitat.com/artist-turns-urban-trash-into-amazing-animal-murals/big-trash-animal-by-bordalo-ii-16, accessed November 30, 2018.

[xiv] “Bordalo II: Turning Trash into Stunning Animal Art Pieces,” Interesting Engineering, https://interestingengineering.com/bordalo-ii-trash-into-art-pieces, accessed November 26, 2018.

[xv] Artur Bordalo, “Big Trash Animals,” Bordalo II, http://www.bordaloii.com/#/big-trash-animals/, accessed November 26, 2018.