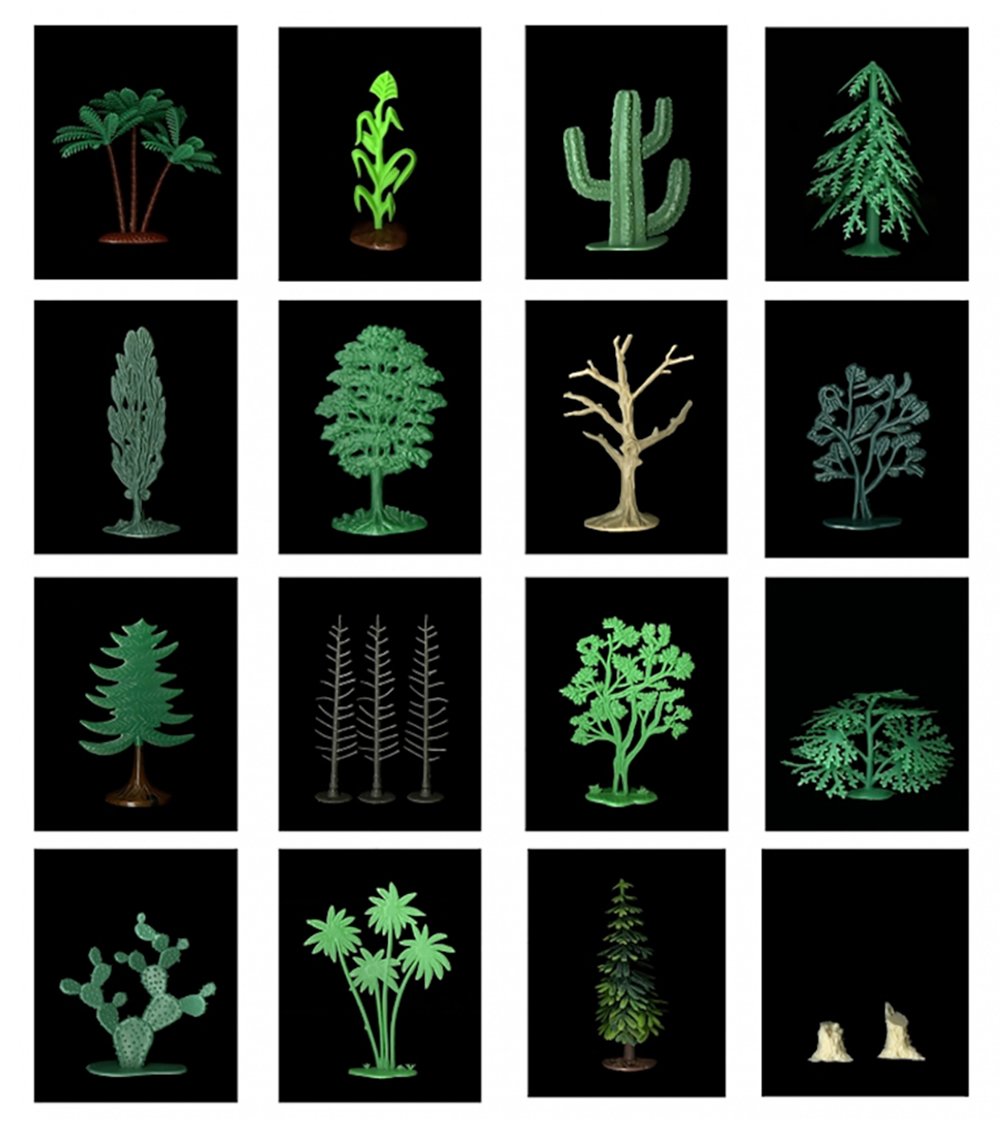

Tom Jones, Ho-Chunk

North American Landscape, 2013

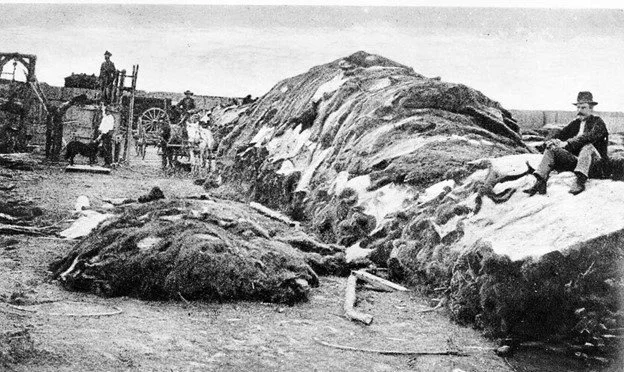

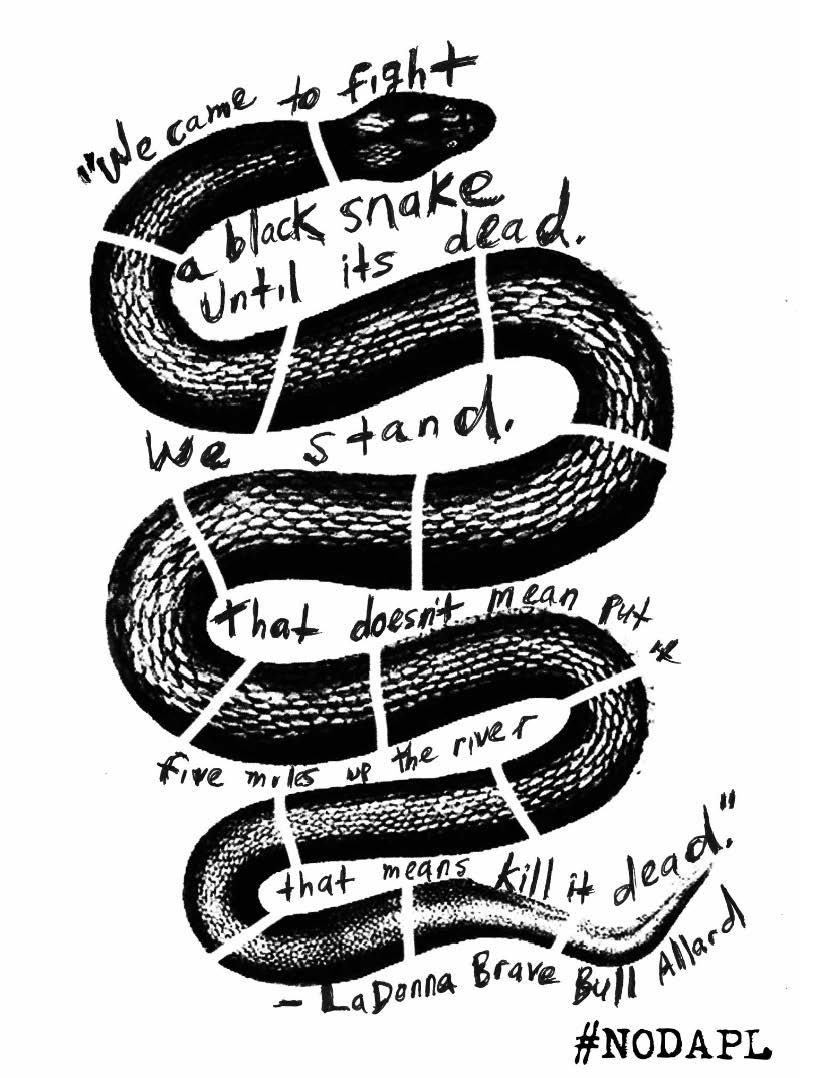

Within the digitally scanned 3D photographs of plastic toys, Tom Jones reimagines notions of what Indigenous landscape art should look like and simultaneously explores the processes of extractive industries in Native American lands. Each photograph represents a different Native American landscape, such as a Hopi or Seminole landscape, which is preyed upon by neoliberal structures fueling consumption and extraction of Indigenous lands. Similar to the invasion of sacred spaces through the Dakota Access Pipeline, where the oil industry sought to exploit the lands of the Oceti Sakowin for the sake of extraction and profit, Jones posits each tree, plant, and stump as distinct from the original landscape. Consequently, Jones helps the viewer envision the disembodiment of Native landscapes through separating the toy from its surrounding landscape and using toys made of plastic—another extractive industry. Label by Eliza Madison