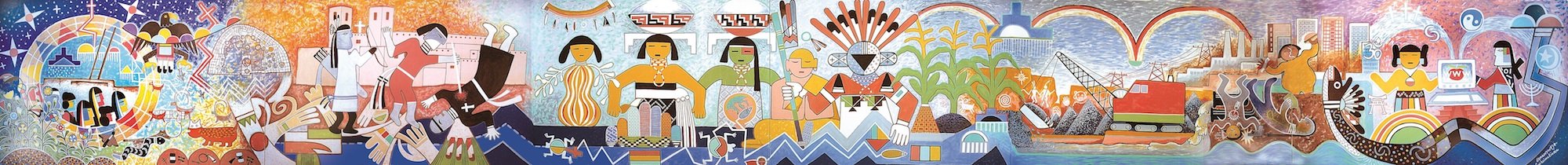

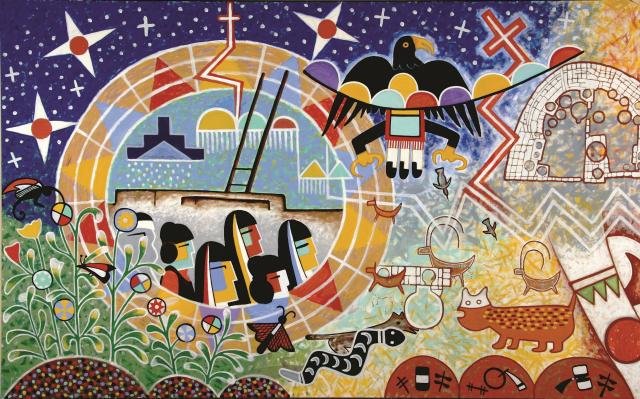

T. R. Chouhan, Indian

Bhopal Gas Tragedy

This is a painting by T. R. Chouhan, a previous MIC plant director at the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal. Chouhan was always an outspoken critic of the plant and gave accounts of the mismanagement and disregard for safety that ultimately led to 40 tons of toxic Methyl Isocyanate gas being released into nearby communities, killing or injuring hundreds of thousands of people. Here he depicts this hazardous industry as a demon that has invaded a body and is spreading poison into the environment. On the right side of the picture plane we can see scenes of destruction and death. Chouhan continues to try and call attention to the harm this disaster is still causing. Dow, which now owns Union Carbide, refuses to help the victims or clean up the site and actually promised more investment in India’s economy if the event were to be forgotten. This tragedy has far reaching consequences: in surrounding communities cancer is common, women continue to give birth to children with birth defects, and the water is contaminated; almost 40 years after the leak itself, these chemicals (and Dow by refusing to take responsibility for the accident) are still harming people. Label by Savannah Singleton